The loss of a loved one comes with emotions that may feel impossible to put into words. However, the stages of grief do just this. Five words, and the stages they describe, have become the common standard for what we may go through when grieving a loss. But where did this standard originate from? Who decided that this was the grieving “norm”, and can we deviate from it ourselves after suffering a loss?

In 1969, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross released the book On Death and Dying, containing her Kübler-Ross model, or as we know it today: the five stages of grief (also sometimes called the DABDA model). She created this model from research in the form of interviewing more than 200 individuals with life-threatening illnesses on their experiences. While we typically think of these stages as something for the bereaved, it’s important to note that they were created for the terminally ill. And though this model is often seen as a sequential process, it’s actually a non-linear path, where emotions will come and go as time goes on.

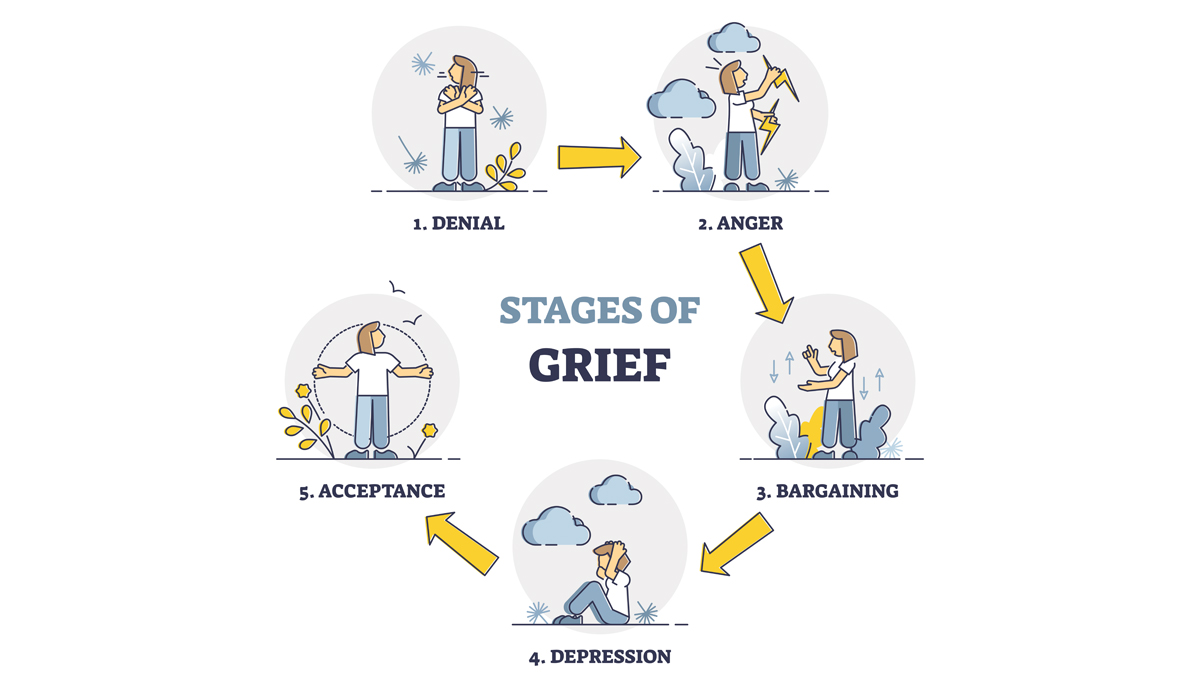

The Stages of Grief

Denial

Denial isn’t just refusing the loss that has happened. It can also feel overwhelming and like the world has become meaningless. Feelings of shock and numbness occur as our bodies and mind only let in as much emotion as we can handle. As this shock fades away, feelings that have been suppressed will begin to surface.

Anger

As we begin to feel emotions again after a loss, anger may rise above the rest. Anger after a loss may have no actual direction and can target a variety of areas in our life including friends and family, ourselves or our loved one lost, even just the world in general. It could be said that the anger we feel after a loss is just one more indication of the strength of our love for that person.

Bargaining

After a loss, it’s only natural to want life to go back to the way it was. Statements like, “If only we could go back in time,” or “What if this never happened?” become ways to try not to feel the pain of a loss. And by remaining in the past, we can avoid some of the hurt—temporarily.

Depression.

While bargaining focuses on the past, depression is all about the present. Grief may be felt deeper than it was before. With the permanence of death, it may feel like the depressive thoughts will last forever. And while typically in life depression is seen as something to be fixed, after a loss it’s an integral part of healing.

Acceptance.

This shouldn’t be confused with one being okay with a loss but it’s acknowledging the fact that a loved one is now physically gone, and with that comes a new, painful reality. We may never like this new reality, but it is the one we accept and learn to live with. Acceptance isn’t moving on, nor is it the endpoint of the grieving process. It can be making new connections and relationships, listening to our own needs, or just simply living again—but only doing so after we have grieved.

Whether it’s you or your loved one dealing with a terminal illness or grieving the loss of someone close, these stages can be thought of as a valuable model that shows grief is not just sadness—but a multitude of feelings, emotions, and experiences that will be unique for each person. It’s a tool to help us find greater acceptance as we progress through our grieving journey, one with no end in sight.v